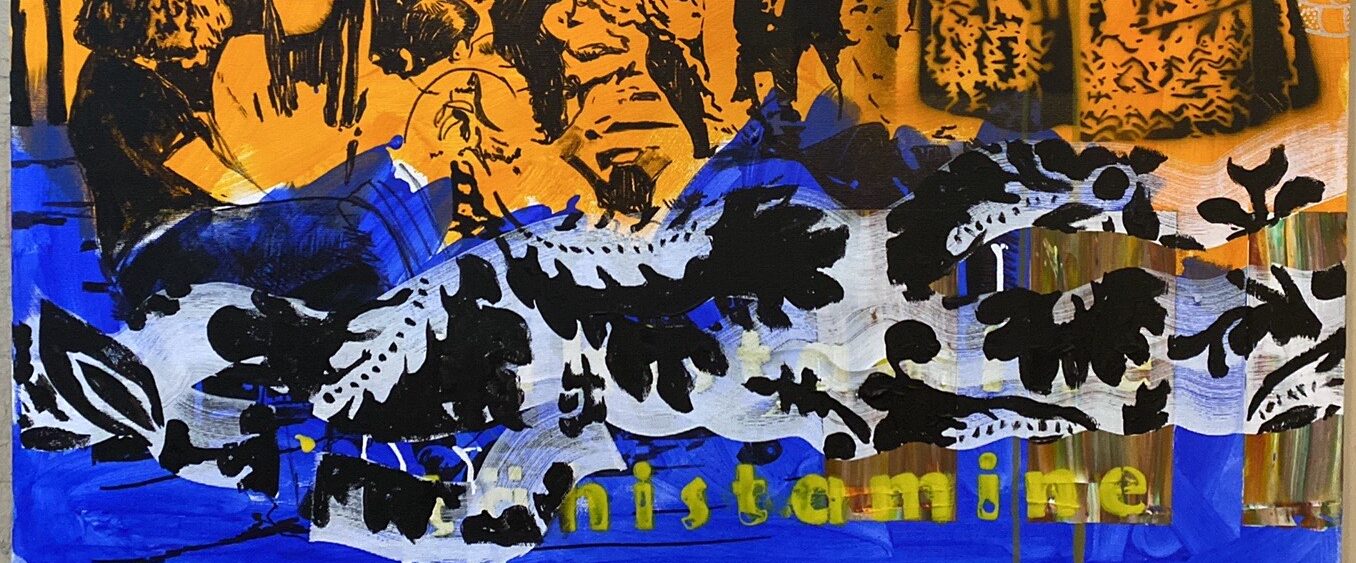

Odds & Ends

– Bob Dylan & The Band, Big Pink, 1967

Bob & The Band are gathered around the table, guitars out,

coffee cups emptied & Garth’s accordion is moving in his arms

like a wiggling centipede. Richard, maybe a bit high already,

is laughing, joking, referring to Bob as an All American Boy,

a title Bob enjoys enough to write lyrics to, tho right now

he’s poking at his typewriter – he’s like a jaybird pecking seed

on a ledge – & editing the words to I Shall Be Released while

Robbie’s listening to the way sparrows, in their chirping

trifling w/ one another, resemble gossips – women chirping

& fretting even – & he says to no one in particular, gosh, it’s

like a small-town clothes line saga, another title, & Bob grabs it,

quickly jots it down in a small notebook where he’s also composed

Crash on the Levee. & Rick’s humming Just Like a Woman –

his cracked voice, elegiac, & he’s recalling holding Grace, who

would be his wife in 68,’ as she wept then laughed, after slipping

on a wet stone as they hiked through a swift Catskills brook

& she fell into it, got wet. Oh the sadness in her eyes – he

felt it – as she cried quickly, prophetically, as if seeing how

they’d end, how he’d die after a last show at the famed Ark

in Ann Arbor in 1999 – & that Rick had proposed to her – she

was re-living it – after a horrible car accident that saw him

wrecked, his neck broken. & at their marriage, at the Church

of the Holy Transfiguration of Christ-on-the-Mount, here

in Woodstock, Rick, still in a neck brace. & that in wetness –

that strange consciousness of surrender into fate’s baptism –

we become vulnerable to memory. & Rick saw her in it, their

memory of the past, their future. & Rick, already hearing

how he’d sing, It Makes No Difference. Then they got up,

laughed at being wet. Hiked back up the steep hill to where

the Black 50’ Hudson Hornet sat parked. Drove it back to

Big Pink. Elliott Landy there, shooting some photographs

while Levon made a ham sandwich. Now Rick comes thru

the door w / Grace – they’re both all wet – & Garth tells

the boys he wants to drive in to Woodstock, to the bakery,

to purchase some deserts to eat but I’m now entering it,

this poem, ‘cause Bob’s just jumped up from the table

& he’s ready to record something. & gazing over Bob’s

shoulder, I see what he’s written in the lyrics, by black pen:

& I shout out to Garth, hey G – you ain’t goin’ nowhere.

This Wheel’s on Fire

It’s a morning in West Saugerties, New York,

& Dylan and The Band are at Big Pink,

that house up in the Catskills behind trees

where, when the hills scratch the sun there is fire,

& the dirt road up to it suddenly catches flame,

& Rick Danko’s fiddling w/ an ominous

piano riff while the others are tuning up.

Levon’s searching for his drum sticks & telling

Garth a joke about shooting old possums

w / a buddy when they were kids in Arkansas,

& someone’s left the kettle on & its wheezing.

The Band’s car, a 54’ Mercury, sits parked,

summer sunlight blistering it, roasting it hot.

Robbie’s sipping coffee, changing a string

while reading a headline in the newspaper

about a riot in Roxbury following a welfare

sit-in, & maybe Detroit’s about to combust

as the July heat turns serpentine, wicked.

Who ever believed bolts could secure a car’s

wheel, or a world’s fixed guarantee intact?

Sometimes the world’s wicked messenger

ignites forward, asking who among us will see it.

Who among us will deem it a tale to tell?

& Richard’s stretching his long, lanky arms

up high enough that, w/ his drunken finger tips,

he can touch where Heaven’s fiords fume.

Dylan’s hearing a cicada in the trees above him

& it is tormenting enough, is Biblical enough

& is grinding enough like a wheel spinning off

a car that he stills himself hard, listens to it,

lets the fire enter his eight fingers while he sits

poised at the typewriter. Somehow, somewhere

the cicadas sizzling, coupled w / Rick’s fingers

crossing over the piano keys in that ominous

monotone of frenetics, adrenalizes Dylan

so that as he types it, these words of the song,

This Wheel’s on Fire, he becomes suddenly

prophetic, can feel the wheel of life in its

reckless bleak turning, can sense the break-

down of the silly, accessorized summer of love

& the way greed disfigures human consciousness

so that it tears the fabric, the entire soft lace

of civility apart so that the lace is now confiscated,

is stolen & wrapped in a sailor’s knot & hidden

in the case of the disguised one, the shadow –

whom Dylan perfectly imitates in this song –

whose whole aim is to get another’s evil favors

done.

Ken Meisel is a poet and psychotherapist, a 2012 Kresge Arts Literary Fellow, a Pushcart Prize nominee and the author of eight books of poetry. His most recent books are: Our Common Souls: New & Selected Poems of Detroit (Blue Horse Press: 2020) and Mortal Lullabies (FutureCycle Press: 2018). His new book, Studies Inside the Consent of a Distance, will be published in 2022 by Kelsay Books. Meisel has recent work in Concho River Review, I-70 Review, San Pedro River Review, The Wayfarer and Rabid Oak.