Russ Thorburn – Editor

Alex Vartan Gubbins – Editor

– – –

ISSUE 5

John Freeman

Paper Sleeves: A Brief Memoir of Yazoo Street

Maybe it’s none of my never mind,

but can a word like “exalt” exalt?

It’s hard bread Eliza carries,

a baguette, and hard to believe

that the non-sequiturial power

of song’s shambolic portraiture

sustained her half a century.

It’s hard to call it a hard life.

She carried bread in a paper sleeve

down Yazoo Street where

everybody knew her name

and knew enough to look away.

Yazoo Street circa whenever.

Does a word like “circa” evoke

whenever in the widow’s mind?

Whenever in the widow’s mind

it rains, I, William with the drunken head,

and Eliza with the hard bread

appear in a hallway halated

by sallow light and bilirubin

slow to clear. What the widow’s given

to the town is the clever clapback

rain and the enigmatic aura

that shrouds each lost companion

in mist that burns from puddles

pooled in Yazoo Street.

But the scandal and the talk of talk,

Eliza in the widow’s doorway,

and I, William with the drunken head

humming the melodic sorrow, the dissonant

sorrow that drowns in motorcars’

drones and itching gramophones.

Eliza with the track marks on her forearms

and bruises like little Pegasus tattoos

as we scratch and scratch

the song for the meaning of scandal.

It isn’t hard to scandalize the provincial

imagination of the citizens of rain-glazed

Yazoo Street, feudal in their economy,

cruel in their embarrassments.

Appended to negative declarative syntax,

they are their rumors—

It’s none of my business, but…

Exuberance, exuberance, how

does a word accrue its power? Wanton,

slattern, widow. I should dispel

the exuberant rumor, the wanton rumor

that I was once in love with her.

In fact, I still am, though rain-glazed

Yazoo Street is irrecoverable

as the origins of Troy, as the many versions

that were sacked and burned

and rebuilt into Ilion of Epirus, record

sleeves, and bitter rock n’ roll.

Cal Freeman (he/him) is the music editor of The Museum of Americana: A Literary Review and author of the books Fight Songs (Eyewear 2017) and Poolside at the Dearborn Inn (R&R Press 2022). His writing has appeared in many journals including Atticus Review, Image, The Poetry Review, Verse Daily, Under a Warm Green Linden, North American Review, The Moth, Oxford American, River Styx, and Advanced Leisure. He is a recipient of the Devine Poetry Fellowship (judged by Terrance Hayes), winner of Passages North’s Neutrino Prize, and a finalist for the River Styx International Poetry Prize. Born and raised in Detroit, he teaches at Oakland University and serves as Writer-In-Residence with InsideOut Literary Arts Detroit. His chapbook of poems, Yelping the Tegmine, has just been released.

Ken Meisel

Odds & Ends

– Bob Dylan & The Band, Big Pink, 1967

Bob & The Band are gathered around the table, guitars out,

coffee cups emptied & Garth’s accordion is moving in his arms

like a wiggling centipede. Richard, maybe a bit high already,

is laughing, joking, referring to Bob as an All American Boy,

a title Bob enjoys enough to write lyrics to, tho right now

he’s poking at his typewriter – he’s like a jaybird pecking seed

on a ledge – & editing the words to I Shall Be Released while

Robbie’s listening to the way sparrows, in their chirping

trifling w/ one another, resemble gossips – women chirping

& fretting even – & he says to no one in particular, gosh, it’s

like a small-town clothes line saga, another title, & Bob grabs it,

quickly jots it down in a small notebook where he’s also composed

Crash on the Levee. & Rick’s humming Just Like a Woman –

his cracked voice, elegiac, & he’s recalling holding Grace, who

would be his wife in 68,’ as she wept then laughed, after slipping

on a wet stone as they hiked through a swift Catskills brook

& she fell into it, got wet. Oh the sadness in her eyes – he

felt it – as she cried quickly, prophetically, as if seeing how

they’d end, how he’d die after a last show at the famed Ark

in Ann Arbor in 1999 – & that Rick had proposed to her – she

was re-living it – after a horrible car accident that saw him

wrecked, his neck broken. & at their marriage, at the Church

of the Holy Transfiguration of Christ-on-the-Mount, here

in Woodstock, Rick, still in a neck brace. & that in wetness –

that strange consciousness of surrender into fate’s baptism –

we become vulnerable to memory. & Rick saw her in it, their

memory of the past, their future. & Rick, already hearing

how he’d sing, It Makes No Difference. Then they got up,

laughed at being wet. Hiked back up the steep hill to where

the Black 50’ Hudson Hornet sat parked. Drove it back to

Big Pink. Elliott Landy there, shooting some photographs

while Levon made a ham sandwich. Now Rick comes thru

the door w / Grace – they’re both all wet – & Garth tells

the boys he wants to drive in to Woodstock, to the bakery,

to purchase some deserts to eat but I’m now entering it,

this poem, ‘cause Bob’s just jumped up from the table

& he’s ready to record something. & gazing over Bob’s

shoulder, I see what he’s written in the lyrics, by black pen:

& I shout out to Garth, hey G – you ain’t goin’ nowhere.

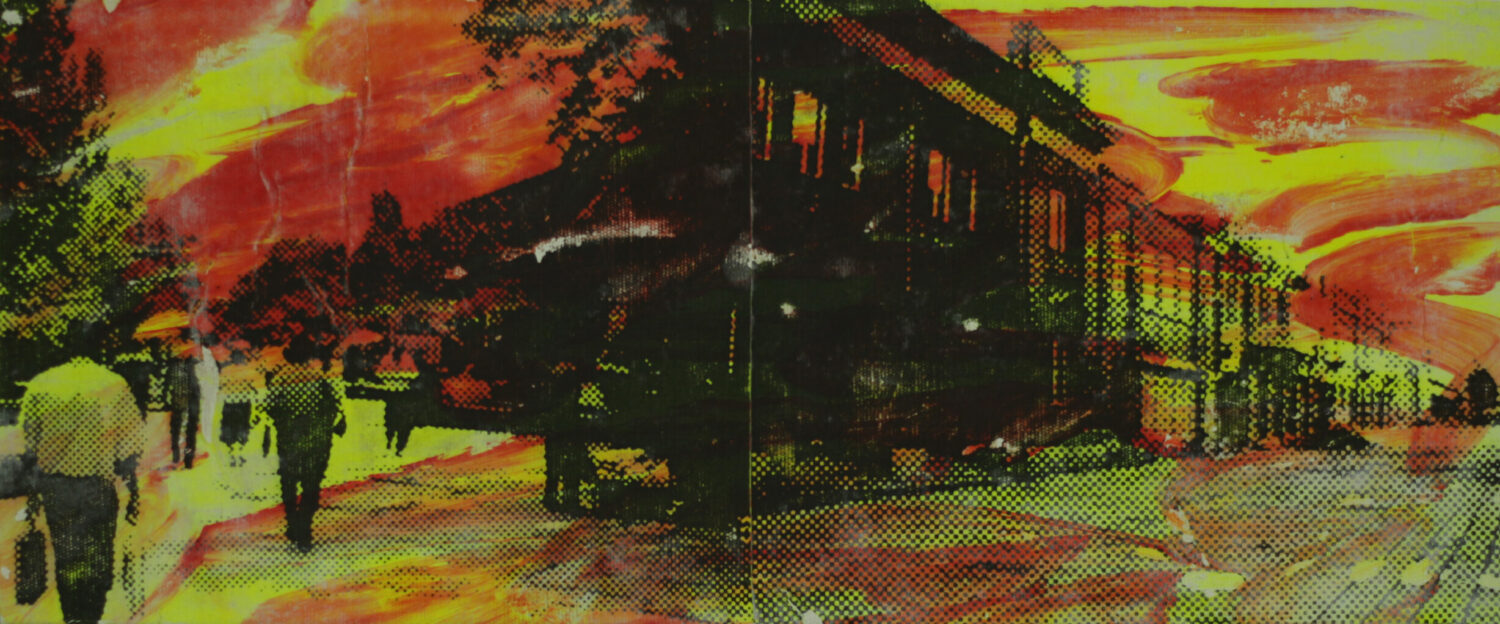

This Wheel’s on Fire

It’s a morning in West Saugerties, New York,

& Dylan and The Band are at Big Pink,

that house up in the Catskills behind trees

where, when the hills scratch the sun there is fire,

& the dirt road up to it suddenly catches flame,

& Rick Danko’s fiddling w/ an ominous

piano riff while the others are tuning up.

Levon’s searching for his drum sticks & telling

Garth a joke about shooting old possums

w / a buddy when they were kids in Arkansas,

& someone’s left the kettle on & its wheezing.

The Band’s car, a 54’ Mercury, sits parked,

summer sunlight blistering it, roasting it hot.

Robbie’s sipping coffee, changing a string

while reading a headline in the newspaper

about a riot in Roxbury following a welfare

sit-in, & maybe Detroit’s about to combust

as the July heat turns serpentine, wicked.

Who ever believed bolts could secure a car’s

wheel, or a world’s fixed guarantee intact?

Sometimes the world’s wicked messenger

ignites forward, asking who among us will see it.

Who among us will deem it a tale to tell?

& Richard’s stretching his long, lanky arms

up high enough that, w/ his drunken finger tips,

he can touch where Heaven’s fiords fume.

Dylan’s hearing a cicada in the trees above him

& it is tormenting enough, is Biblical enough

& is grinding enough like a wheel spinning off

a car that he stills himself hard, listens to it,

lets the fire enter his eight fingers while he sits

poised at the typewriter. Somehow, somewhere

the cicadas sizzling, coupled w / Rick’s fingers

crossing over the piano keys in that ominous

monotone of frenetics, adrenalizes Dylan

so that as he types it, these words of the song,

This Wheel’s on Fire, he becomes suddenly

prophetic, can feel the wheel of life in its

reckless bleak turning, can sense the break-

down of the silly, accessorized summer of love

& the way greed disfigures human consciousness

so that it tears the fabric, the entire soft lace

of civility apart so that the lace is now confiscated,

is stolen & wrapped in a sailor’s knot & hidden

in the case of the disguised one, the shadow –

whom Dylan perfectly imitates in this song –

whose whole aim is to get another’s evil favors

done.

Ken Meisel is a poet and psychotherapist, a 2012 Kresge Arts Literary Fellow, a Pushcart Prize nominee and the author of eight books of poetry. His most recent books are: Our Common Souls: New & Selected Poems of Detroit (Blue Horse Press: 2020) and Mortal Lullabies (FutureCycle Press: 2018). His new book, Studies Inside the Consent of a Distance, will be published in 2022 by Kelsay Books. Meisel has recent work in Concho River Review, I-70 Review, San Pedro River Review, The Wayfarer and Rabid Oak.

Robert Thibodeau

This Heart Shaped Wheel of Fire

He who doesn’t make mistakes

own up, forgive, for heaven's sake;

attachment, anger, hate their fate

till purified in fire by heaven, wake.

Love's fire enlivens, quickens

future deeds, footsteps to heaven.

Truth alone frees but’s so hard,

till the fire returns joys wings to Heart,

Breath to the Soul, love to the art.

Learn from the mistakes, then

no mistake at all. From big Love

and Truth, vow never to part.

I first realized poetry as an art work when attending Wayne State University and meeting cliches of poets making the scene, seemingly influencing all the creatively smart thinkers whether spiritual or materialistic. Poems then revealed secret truths about the world, self and other; how to interact, romance, dive deep and fly high.

Soon I met and partied with John Sinclair in Ann Arbor, a hundred of his friends, in the front row at the free John concert with John Lennon singing. Later I’d hang with artists and poets at Artist’s Workshop Wayne State University, the MC5 in Ann Arbor and in time at Mayflower Bookshop. I learned to write about what’s close and near and not fear stars overwhelming and tearing me from you, wherever you are!

Russ Thorburn

This Wheel on Fire

This wheel on fire allows me to remember

the girl who slipped with me into the river

full of frogs and cicadas flying about her neck.

Her sunburned eyelids lowered as she gifted me

with her bare ass diving into the muddy mirror.

Believe me, old prophets of love and pestilence,

I always looked for redemption in her shoulders

of champagne and sunsets brightening her smile.

Richard Manuel grinning like a bear after writing

a song with Bob Dylan, and my hands reaching

for her body as if the heart were igniting this desire

wherever my fingers crossed. Let me find a laughing stream

to immerse our love and watch a thousand birds

circle the earth. A dog barks somewhere in the distance.

There’s so much lost in an accordion rippling.

Walking down Parnassus Road, I feel thunder under my skin,

wanting her arms wrapped around my shoulders.

All that remains for me is to walk until

she appears naked as the Old Testament, and her tits

to light another fire on guitar, with Robbie dampening

the strings with the heel of his palm. There can be no true

path to love, but I keep hiking down Parnassus Road,

finding that I never loved her enough.

Notes on the Poem: Ken Meisel told me of his visit to Big Pink, and suddenly I was walking down Parnassus Road with him to that strangely colored house. An unearthly pink, if you could call it pink at all, but think of Levon on drums, Bob Dylan upstairs in the kitchen typing up another song with all his misspellings. These compositions rose up from the basement in what would be called The Basement Tapes. One of them would become “This Wheel’s on Fire,” and that song burned through me remembering a loved one. I felt all the love I had for her preach to me somehow in a Biblical sense. There was a thunder under my skin, with “This Wheel on Fire.”

Russell Thorburn lives in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The first poet laureate for the Upper Peninsula in 2013 and a recipient for a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, he has published five books of poetry, including Let It Be Told in a Single Breath, Cornerstone Press, University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. He is an independent manuscript editor and consultant whose clients have published books in the U.S. and Canada.

Nancy Owen Nelson

Skinny Dipping When I First Arrived at Auburn

Things were different then, sudden freedom,

southeast Alabama sticky nights, mosquitoes,

lukewarm beer dribbling down naked breasts,

all lost, changed, yet worlds to be explored.

Here, I found, professors were not to be feared,

but to be joined in a party—a lake house with Dylan

blasting from a LP album through open windows,

frayed curtains blowing out into humid air.

Most times it started a beer-fermented brain,

unfettered by Jesus or Daddy watching.

Clothes on, then, a second time, pulled off

under cover of water, thrown on a dock,

made a squishy sound as they landed, panties

and all, on a slippery surface. Then next time,

ease of stripping, shirt and jeans, shorts, or dress

thrown carelessly on the grass full of chiggers,

Southeast Alabama’s gift to skinny dippers.

Who cares about the red rash, the itching

The next day? It was all worth it—those moments

before it was time to return to study Paradise Lost.

We were Milton’s fallen angels.

Pandemonium became a new heaven.

Nancy Owen Nelson’s poems have been published in a number of journals. Other publications also include her memoirs, Searching for Nannie B, 2015 and Divine Aphasia: A Woman’s Search for Her Father (2021),her chapbook, My Heart Wears No Colors, 2018, and Portals: A Memoir in Verse, 2019. Five Points South: Poems from an Alabama Pilgrimage (2022) was selected as Book of the Year by the Alabama Poetry Society. She currently lives in Florence, Alabama, where she serves as Executive Director of 7 Points Press.

ISSUE 4

Robert Fanning

Fisher, Man

Man’s adrift at dawn in his blue canoe.

His line bobs near the pier.

On shore, a stray barks

at its long shadow on the sand.

Man lolls in half-sleep. Wave-laps

lull him. Toward him, a corpse

glides, splayed in a black suit.

At the bulk of this small dark

berg thunking his hull, Man wakes.

Out over the side of his boat, Man eyes

the pecked translucent blue of the dead man’s face,

his stiff hand trailing a ripnet

of bright green weeds.

From his mouth, minnows spill

like prayers. Man shudders at the eyes—

bulbous and wide to the sky—but he glows too.

This is his life-fish.

Wobbling, Man reels, bending

to slip bare arms around the corpse,

lifts him into the boat.

A veil of mist. Man

hoists the dripping corpse

onto his shoulders. Then drags his catch

like some drowned groom

onto the beach.

Two Drifters

Corpse and Man float on their backs

in bed, drifting on sleep's reedy river.

One breathes. A blessing of air,

a breeze enters, caressing the flesh

of dead and living alike. Man dreams—

Corpse sinks in fragments: his torso and limbs

broken stones, ruins strewn

on red sheets. A riverbed. Dreaming, Man

sings: I'm crossing you in style someday.

Corpse floats toward the surface light of

Man's mouth. Wherever you're going,

I'm going your way. For a moment,

they harmonize. Come sunrise,

eyeless, fishpecked: Corpse reassembles and dies.

There's such a lot of world to see. And so to realize

the day: Man wipes his eyes.

So Many Empty Shoes

Waking with a start, Man stumbles down

his dark hall to piss, his house littered

with all manner of empty shoes.

Whose shoes, whose shoes. Man mutters

to himself, falling into a layered heap

of loafers, boots, pumps, sneakers,

flip-flops. He clambers back across

the mountain of shoes to where Corpse lies

in his bed, Corpse now Man's father

and Man a boy again—frightened by thunder.

May I crawl inside with you? Man asks,

nudging his father, now Corpse again.

Corpse doesn't stir. Man turns, gazing

at the floor, where in each lightning flash

he sees no shoes, though his feet are sore.

Robert Fanning (he/him/his) is the author of four-full length poetry collections: Severance (Salmon Poetry 2019), Our Sudden Museum, (Salmon Poetry 2017), American Prophet (Marick Press 2009), and The Seed Thieves (Marick Press 2006) as well as two chapbooks, Sheet Music (Three Bee Press 2018) and Old Bright Wheel (The Ledge Press 2002). His poems have appeared in Poetry, Ploughshares, Shenandoah, The Atlanta Review, The Cortland Review, Rattle, Waxwing, failbetter and many other journals. He lives in Mt. Pleasant, MI.

Denise Sedman

The Blue Marble

My sister stole a blue marble

from a Chinese Checker’s game,

glued it on the lid of a Popsicle-stick box,

Made one-word-sheets of

paper, tore them to pieces,

stuffed better-day dreams inside.

No one cares. Not one bit at all.

Go mumble to yourself,

look outside through bars,

watch Soap Operas all day,

make a gimp for your sister, but

don’t open a locked door.

When my sister said:

“I’m going to kill myself.”

Our father said:

“I don’t give a fuck. Kill yourself.

Get the fuck out of here.”

How the knife got back in the drawer

before she shimmied next to me in bed,

I don’t know,

but I died a hundred deaths. Your Husband Said … It didn’t happen

when there was a tsunami

in the Indian Ocean

Waves went above 40 feet

as this uncontrollable disaster

became your wake of devastation

Then you peed your pants

became rigid, disconnected

readied for an institution

He prays you’ll recover forever,

but it’ll happen again,

he’ll give you more chances

The Human Condition

RIP Anthony Bourdain

June 25, 1956 to June 8, 2018

It’s all about blood, organs, cruelty and decay;

danger, risking the dark, going to bed

with sweats, chills and vomits.

He wanted it all:

the cuts and burns on his hands and wrists,

ghoulish kitchen humor, the free food,

rigid nerve-shattering chaos;

the sheer weirdness of kitchen life;

a last stop for misfits,

the dreamers, crackpots, refugees,

and sociopaths; roasting bones,

searing fish, and simmering liquids;

the noise and clatter, the hiss and spray,

flames, smoke and steam, he said

it’s a life that grinds you down,

you’d think chefs would kill one another with regularity;

jam a boning knife into another cook’s rib cage,

or brain him with a meat mallet, but not dry age.

Denise Sedman is an award-winning poet from the Detroit area. Recent work has been featured in San Pedro River Review, New Verse News, and Gravel Literary. She’s included in the 2017 feminist anthology Nasty Women Poets by Lost Horse Press.

Ken Meisel

The Angel of Doo Wop

snaked up to me in a dive bar

somewhere down south,

and it placed my finger over the knob

that punched I Only Have Eyes for You –

by the Flamingos – so that I could hear

the echo of harmonic voices

lifting up and humming in the stars

over a swamp behind us,

and a lonesome woman, a blond,

gazed over into my eyes –

she was probably sensing

something real, some signal

from the heart

she felt, or remembered,

as millions of people go by

but, gazing into me, they all

disappeared from view

because, her eyes said to me,

I only have eyes for you.

And I leaned across the wooden

bar, gazed back into her

earth angel eyes, as if

telling her she would be

the only one I adore.

Then the Five Satins, In the Still

Of the Night, played –

a man in a corduroy coat

had shuffled over and pressed it to play,

and the echoes

of the glassware tinkling in the bar

pulsed like stars, like eyes

watching over us: over

our sad beauty, our

inescapable matter,

our nights in May when we

claim our love for one

another and, in the still

of the night, a man outdoors –

we could see him through

the glazed bar window –

stood rocking on the step

of an empty building

playing his exquisite saxophone

to that part of Being he,

himself, could never play –

except by and through

the sublime strobe lights

of God

flooding his horn

with all the incandescent light

that the stars and fate

are made of,

and the sad doo wop angel

leaned over to me,

drink in hand, and said,

you know Kant was correct

when he mumbled

beauty is the only finality here,

and the song on the juke box

was Come Softly to Me by the Fleetwoods,

and the girl’s voices,

silken across the mic,

thrilled me

until I was a mirror

somersaulting me back

to my own desire –

to the love songs

of winsome school girls

with scarlet ribbons –

and the angel pointed me

toward the infinite veils

of beauty that, in this bar,

because they are

from the other mansion

on the hill – that house

we can’t see but only feel

with the heart’s

espionage of poetry –

are absolutely

without equivocation,

without reflection,

without hesitation

born from that light

most glad of all,

and, because of that –

because they caress

and baptize us

with magic –

they’re everlasting.

The Caretaking Angels Encounter Me

This was on a foggy winter morning,

on the back streets of Venice Beach

where the meth addicts hid in messy

cars and did their business while the city

of Los Angeles ticketed their junked

cars for illegal parking. I was standing alone

under a strange tree, studying a lovely

yellow flower’s pointed tips while

the innocent children chased one another

across a play ground in a spirited game

of hide-and-seek or rag tag – it was difficult

to figure it out. Along Abbot Kinney Blvd

I watched a man watching a woman as

she passed quickly by him in her yoga pants –

she was chirping steadily on her cell phone

to someone – and some part of him

began his initiatory descent into hell

while the muscle men on the wild beach

lifted weights together, tugged and pushed

the barbells high up, into the paradisal

pacific sky so dense with cataclysmic clouds

marauding over the ocean’s lathering

concourse of waves, crashing to shore.

And men, dressed shabbily in drag,

abolished themselves to a kind of

farcical ornamentation because they

were dressed in littered fabric and large

black refuse bags, and when I gazed back

at them, before leaving the beach, I

thought they resembled a conjuration

of dumpsters. Some assemblage of plasma.

Along Sunset Avenue, I watched a boy

inhale the meth by himself like a feral

pariah dog. His gray fingers, cupping

the glass pipe with a sphere on its end

where, in the after burn, a smog escaped

just after he pulled his slanted mouth

away from it, burning him – seemingly –

in the rancid heat. And when I saw him

light it again, the crystal meth liquefied

and he moved his small yellow lighter

back and forth in front of it as he

inhaled the vapors until his eyes lids

dropped shut like a sickly salamander.

Keats, you know, wrote so dizzy,

mixing the senses especially in that poem

Ode On Melancholy where he asserts

“but when the melancholy fit shall fall

from heaven like a weeping cloud that

fosters the droop-headed flowers all,”

I think he might have been seeing this

boy addict crouching down in the shadows

along Sunset Avenue, near the fast

Pacific Highway, while delivery trucks

thundered past him in dust clouds. I think

I was unstoppable in my own lostness,

clothed in my own vapor when I found

myself adrift in the canals, mesmerized by

the brown saltine waters until it hit me

I was trapped, too, by the distinct boutique

of the abyss. And the boy’s smoking of

meth – like some initiatory departing

of himself into lost vaporization –

turned me obscure and transparent,

like I was just blue condensation, mist, fog.

Nothing left of me but drowsy salt-light.

And, kneeling beside a white flower in a pot,

I felt the structure of the world

bending me down, so fraught with all these

irreconcilable ideas and impregnable deities

without actual names and, while a woman

watered her plants and the silent canals

flowed memoryless – without interpretation –

I became remote, like the meth addict boy,

lost in translation, without prayer. On the

beach, far off, rain collected over the pier

and a police car rode silently up to it.

Another woman, a nightingale, talked

sporadic into her cell phone as I walked

up to the pier to drown myself in haze.

And the Caretaking Angels – those beings

sent to gather all of us poorly born

to flesh again – crouched in ranks along

the shore, readying one by one to cradle

me into their extended gentle arms:

I could see them in the wave’s bloom

and sprawl. And the rain fell silent,

like the hungry splintered spirits of us all.

My Horoscope in a Style of Harry Houdini

The horoscope read, “you wound up

in this situation because somebody

else wanted it.” So let me tell you how

to escape it: you lay the white cloth out

on a table by your bedside. Then you

mix the white powder you have dutifully

purchased from the dealer, in 20-40mg

of water, and, then, filter it through a

small balled up piece of cotton. Then,

take the needle and flick all the air in it

to the top and push it out. Then, with

the red headband in hand, tie it over

the top of your left arm so that a blue

vein bulges out enough to pierce it,

and insert the tip of the needle at just 20

degrees, and, then, inject the solution

into your vein there. In a moment you

will feel a wind to which no angel has

seen or felt. And then you will fall out.

Something in your mind will lose rule.

And then your evaporation, your escape

from all this, will be complete. Yes.

I have told you this to stir your notice –

says Houdini, unwrapping himself

from ropes. This is while I am alone

in a room in Detroit, the old heaters

rattling the building with steam.

And this is at a time when I am without

name or number; I am anonymous.

And to be anonymous is the way that

advantage seizes someone; rules them.

I watch Houdini walk straight up a wall.

The woman downstairs, intoxicated,

starts singing the song La Vie En Rose.

I believe, in her sorrow, she sings it to me.

Houdini sets a cup of tea for us. Says –

and I have captured you, in this drug

imagery, because to escape yourself

is to unravel time. And those who try it,

try it too often with drugs or gambling,

which is a foolish bid for bad blood.

And so you must push yourself in –

to this beer barrel of your body’s jar –

and then tie off where your arms rule

all your certainty, and then you must

insist that someone – your lover is best –

push and lock the top of the barrel over

you, and then secure it tight with nails.

You must be fixed inside a circumstance.

It’s only through fixity we discover a spirit

in us – which must be accessed to escape.

And then – inside the barrel’s prison –

you must see yourself in a vision where

the entrapped light in there is just a

lonely hobo encircling you. And then,

when terror strikes you like a match and

you’re lit aflame – a tree igniting itself as it

stops disputing all that aggresses against it –

you will inhabit the silence it takes to

achieve your horoscope’s benevolent

refrain; this escaping, of another’s wish

for you. And after you have fell to quiet,

which cannot come through injection

but rather, must come from a lawlessness

only a self-devotion provides to you,

let your hands rise up to the lid’s rim

and push it open, for it was always

just a cloud you thought was wooden,

such is the falsehood of all illusion –

just like this selfhood you’re alive in.

Only after will you know a true limit.

And when I blinked my eyes open to

find Houdini in there – in this room

where I believe he died in – all I saw

was a wall clock that read five o’clock,

a Monday. And the river was slate gray.

There was no sign of Mr. Houdini. Just

the sea gulls, wailing their usual song.

Ken Meisel is a poet and psychotherapist, a 2012 Kresge Arts Literary Fellow, a Pushcart Prize nominee and the author of eight books of poetry. His most recent books are: Our Common Souls: New & Selected Poems of Detroit (Blue Horse Press: 2020) and Mortal Lullabies (FutureCycle Press: 2018). His new book, Studies Inside the Consent of a Distance, will be published in 2022 by Kelsay Books. He has recent work in Concho River Review, I-70 Review, San Pedro River Review, The Wayfarer and Rabid Oak.

Issue 3 – Latinx

Angela Trudell Vasquez

Arboretum

Frames Mexican bones

bodies who built railroads

with broken backs, raw hands.

An 1880 census conceals us

carving holes in steel cars,

for light, night air, hanging

hammocks for sleeping wives

to rock under galaxies.

One woman rides the continent

follows her man from Zacatecas.

Thighs astride her clacking motorbike.

Belly swings on a swing sways on the rails until…

Where they lived in box cars until kids were grown.

Where postpartum was unknown

and unbalanced women got sent back.

Where my grandma, her cousins

hid on the school hill to eat quesadillas.

Neighbors claim the old man rode with Pancho Villa

when men in suits leap off skyscrapers in New York.

Where my mom and tia pretend not to speak English

teasing shopkeepers on the square.

Where my dad ran cross country to escape

those fences, farmland until he broke –

a mahogany streak on burnt clay tracks.

Where my uncle strove through bullets in Vietnam

dragging his buddy to the helicopter.

And grandmothers trade apples for pears

fingertips and ashy wrists

dig out change at the market,

dole out tortillas during meals.

One hand on the open flame,

one hand flutters holds the blue house dress.

Where peony roots divide on their own

sparking an arboretum of sweet pink light.

Whose perfume carries itself uptown

to the courthouse in drafts with garlic and chile.

Where my sister came the day my grandfather was buried.

Water gushing graveside.

And summers meant volting between family houses.

Rhubarb sticks dipped in bone white sugar.

Rope swing thigh burns. Treasure hunts in the gully.

Where I visit now water their parched Easter Lilies

as they lie beneath the grass.

Thank them:

for surviving Midwest winters, wars and lynchings,

for firewood split, mole recipes on parchment,

for raising people who love so much it hurts to swallow,

for lessons on how small caramel women united overcome great sorrow,

for sharing their one red lipstick and rose hand lotion when I was a girl flowering.

Born at a Funeral

Caught, under the bed

baby dolls propped on pillows

stuffed animals against dark pink velour.

Her black curls bop, she reads

Cinderella to her “dollies”

in a voice husky from lack of use.

She lies on her stomach. Ankles twist.

I spoke for her before she spoke

for me when bus stop bullies lobbed spit ball bullets.

Easy target: trumpet case, school books,

extra credit books, glasses, braces, silent.

Little girl born at a funeral

when dirt clods hit the casket.

Her entry on a flood of salt tears, a family’s

wails of grief. Fall ginger leaves scatter our names.

When she began to open her mouth

she wrote stories for her baby dolls.

They rode horses, served tea, played

mass using pickle slices for the host.

Her mother called her father

and began to weep over the wires

looping commas of sound

downtown to our house,

“She can talk. She can sing!”

Sea Burial

Backpacks, a week of groceries, no hospital

for 200 miles, no wheels, I survived –

on the island where once in a clearing

we came upon an animal meeting,

hooves and feathers flee, mass exodus.

There lies part of me, my man –

wedged beneath blinding white rocks.

Body whispers, blood and rot.

Until sediment slides down

the fifteen-foot cliff back to the sea.

Campfire ashes circle the base.

Where pelicans preen and eagles train

to feed, is our born too early zygote.

My two became one.

Female island ghosts told me

sit in the water let life wash out and back

cool stone slabs your throne. We know.

A sea burial. A hollow tree.

Limestone markers.

Dana Maya

Nochebuena (December 24th) for Gloria, mi mamá

I’ve felt you shaky for days.

It’s the December gathering of lives in your body. You are making Chiles en nogada:

soaking almonds & peeling the golden skeins from their bodies, white like tiny doves.

You place pomegranate seeds, huddles in their garnet amniotic sacs.

You want there to be bounty. You are trying not to breathe.

Come, I take your hand & say.

I’ve brought a book, a calendar of secular prayers, almanac for abstinent believers,

We who don’t say god, but hold hard to our holy.

I read the entry for Dec 24: Slowly, on the soft bed, I apply gentle, steady pressure.

If we place the words just so, there is divination.

Your eyes go slack & wet.

I leech your tears to balance humors. I am sorry my only medicine is this crude & ancient, dirty & dangerous. I’ve only ever known this cure: homeopathy, Like with Like, Hair of the Dog.

You tell me that every year on Dec. 24, when you were small, Abuelita would tell you

The Three Kings cannot come this year

All she had to feed you was black coffee & bread. Now, almost 7 decades gone, you are still hungry,

hot-bellied & tight-chested for food unoffered, uneaten, ungone.

I see you: the child, my mother

& I see her too: a mother alone, turned to her three children

(Tell me, mi mama, is there anywhere to rest, to breathe

in this small story, is there anyone to be?)

Only here: this bed, almanac, my eyes holding yours. Did you say Los Tres Reyes never showed?

See us now travelling great distances of memory, here we come.

We bear gifts backwards, in our hands.

Not only to you and Tía and Tío, but to Antonia, her face to their small faces,

breaking the news again, of the failure of the 3 kings,

of god himself.

Calling Instructions: How to Live in Sirens

for Tony Robinson & the queer & trans leaders of the Young Gifted & Black Coalition &

#FergusontoMadison, 2015

& for Black Lives. Again, now, still. 2020

Once they call the cops, go ahead & call it murder, cause he’s forced the door &

Inside, shot a black boy once & then five times: torso, shoulder, head

His life pulled up his body, across his unarmed arms & over his crown like an undressing

The long garment of his blood pulled down the stairs & dropped onto the cement stoop

Once they call the cops, go ahead & call it familiar, call this murder home cause we call this

Willy Street the way a boy is named Anthony & called Tony, Terrell

Willy Street, near the Co-op, the Social Justice Center, the street banners that say A Place for All People

Once they call the cops, the dispatch will call him a suspect & the Chief of Police will

call him the subject to the press, the press will call him a black man, though all the neighbors say kid, say teen, say Tony, say Terrell though his friends call him funny & his grandma says gentle

Once they call the cops, the signs will say #TonyRobinson & the chants call What’s his

name? What’s his name? You’ll recall Nina calling young, gifted, and black, your soul intact

& Baraka singing urgent, calling you, calling all Black people calling you, come in.

Once the cops are called, in the carceral state, it’s a world gone siren: the sirens call submit. Lay down.

The Chief & the press & the preachers, the Open Letters call for peace & objectivity & to wait for the facts. You know this song: same damn verses with new Black lives. Same pieties, same lines. You know you’ll be a siren too. Called & calling: saying the same damn shit, one more fucking time.

Once the world’s gone siren, think of Odysseus in that old story. How he survived the calls without crashing on the rocks—Lash your body to the mast. Be the mast. Let your ears flood with cries. Listen & want & want to be released into some final sound. Beg for it. Want it like a new lover & do not submit. Be the rowers. Stop up your ears with wax. Keep rowing. Get to the end of this poem but

don’t stop. Cause this poem is nobody’s son, not a life, not a boy I ever knew. This poem is not that kid.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN Feminist Formations 27:2. https://www.feministformations.org/journal/poesia

My brother tells me he will be a father

A baby:

my brother, a father.

And I a mother

Four years now, two babies

for a dozen years, he’d said

I will not be a father then

I will be a father.

before him, it was me:

I will not be a mother.

I will be a mother.

We were children amid shouts

the closet door dented for a decade,

its off-white metal

a crumpled sheet of paper—

a message gone wrong.

Our parents’ love split

down the middle of our

two small bodies

We fought too—

swore mutual hatred

spells to ward off

larger storms and disasters

Acted the play within the play

puppets tearing at each other’s

hair, not knowing our own plot

Each time we go to love, my brother

we finger the fissure, the cleave running

through our blood. We never say

how it was sweet:

Four of us wrapped together

on the70’s round bed with its

black & white zebra bedspread

Our father, crazy: walking on his hands

down concrete stairs & sidewalks,

stopping for hitchhikers

Before crazy was diagnosis,

we played in the fields of his untamed

mind

Our mami, la Gloria dancing for us

in the hotel room in Yucatan

an underwear joy dance

Until the gardener outside knocked:

a kind intervention

Señora, se puede ver todo…

(she could be seen outside)

She covered her mouth, but the joy in

her big white teeth, showed

I want to tell you yes, my brother

we loved it, loved

us. Yes, we did.

Oscar Mireles History lesson My grandmother Elisa was picketing outside the cattle car trains that were quietly lined up to deport Mexican nationals from Minneapolis Minnesota in the 1920’s Yes, it was her and three other women, my Aunt Juanita and two friends Carmen and Josie Flores they were afraid to hold up their picket signs that protested the mass deportations yet were more afraid worse things would happen if they didn’t do anything A local policeman warned them it would be best if they left otherwise he would be forced to take action but they stood there waving their picket signs like a flag as the last train fell into the sunset Lost and Found Language It started in 1949, when my oldest brother came home from school in Racine, Wisconsin after flunking kindergarten because he 'spoke no English' and declared to my parents that 'the rest of the kids have to learn to speak English if we planned on staying here in the United States.' so my parents lined up the rest of the seven younger children had us straighten up tilt our heads back reached in our mouth with their bare hands and took turns slicing our tongues in half making a simple, but unspoken contract that from then on the parents would speak Spanish and the children would respond back only in English how do you lose a native language? does it get misplaced in the recesses of your brain? or does it never quite stick to the sides of your mind? for me it would always start with the question from a brown faced stranger 'hables espanol? ' which means 'do you speak Spanish? ' which meant if they had to ask me if I spoke Spanish this was not going to be a good start… at having a conversation... my face would start to get flushed with redness and before I had a chance to stammer the words 'I don't'… I could see it in their eyes looking at my embarrassed face searching for an answer that was nowhere to be found as I walked away I knew what they were thinking 'Who is this guy? ' How can he not speak his mother's tongue? ' 'Where did he grow up anyways? ' 'Doesn't he have any pride in knowing who he is? ' or 'Where he came from? ' I tried to reply, but as the words in Spanish floated down from my brain they caught in between my throat, the rocks of shame. I spoke in half-tongue. my future wife taught me how to speak Spanish mainly by being Colombian and not speaking English I had already known the language of hands and love which got me confident enough to reach deep inside myself to rediscover the beautiful sounds and Latin rhythms and although I still feel my heart jump a beat when someone asks 'hables espanol? ' now the Spanish resonates within me and echos back 'si, y usted tambien? ' and today as I talk with the Spanish speaking students at our school they can not only feel my words they can feel my warm heart splash ancient Spanish sounds off my native tongue that has finally grown whole again Elvis Presley was a Chicano In the latest edition of the National Inquirer it was revealed that Elvis Presley, Yes…the legendary Elvis was a Chicano Fans were outraged critics cite his heritage as an important influence I was stunned Can you believe it? Well…I didn’t really at first but then I remembered… his jet back hair you know with the little curl in front sort of reminded me of my cousin “Chuy” Elvis always wore either those tight black pants like the ones in West Side Story or a baggy pinstriped Zoot Suit Pachuco Style with a pair of blue suede shoes to match Then I figured no, it couldn’t be So I traced his story back to his hometown a little pueblo outside Tupelo, Mississippi a son of migrant sharecroppers looking for a way out of rural poverty Let’s see… Elvis joined the army Maybe he enlisted with his “homies” They never made a movie about it But they fought hard anyways I read somewhere that Chicanos have won more Silver Stars and Purple Hearts than any other ethnic group Maybe Elvis was a Chicano I wasn’t convinced yet! Elvis was a Swooner, a dancer, a ladies man and always won the girl that hated him in the beginning of the movie he had to be a latin lover or something even Valentino and Sinatra has a little Italian in them Elvis played guitar like my Uncle Carlos, always hitting the same four notes over and over again But now, I think I have figured it out It was probably that Colonel Parker’s idea to change his cultural identity, since it was just after the second big war and the Zoot Suit Riots it wasn’t the right time for a Chicano Superstar to be pelvising around the Ed Sullivan Show, late on a Sunday night I think it was just a hoax, to convince more people to buy that newspaper If Elvis Presley really was a Chicano He wouldn’t have settled to die alone, in an empty mansion With no family around, No “familia” around Who cared enough…. to cry

Issue 2 – Guest Editor Abayomi Animashaun

D.M. Aderibigne Father's Prayer Because the morning was a bastard, The woman I loved stuffed. Our future in a trash bag, And locked the door. Because I had no scar to show for my wound, I fell on my knees, begging The past to return. The Past returned. “The doctor says he won’t survive,” she said, Putting my hands on her stomach. Few days later, From one of the corridors of heaven, I watched her rock a child—excitement running Across the child’s face. For a moment I forgot He wasn’t hers: ours. The mother Came, took him away—I was reminded That there is no bond Stronger than that which joy and sorrow share. Dear God, when next you pass Through me, pass as a complete story. Night Again, there’s a thunderclap In your womb. On the outskirt of your nightmare Lies a man you’re meant to love. With him, roses are rough, Bullets are beautiful. And as the bandage wrapped Like a bandana around your head Shows: this man’s soft words Have teeth. You rise From the bed, Sit on the wooden Edge of discomfort—it is ripping Your stomach like a hurricane Through a city. You crawl To his wardrobe, Pull out secrets From a drawer; A battalion of strange pills Lays on your palm. You dump the pills in mouth, Drive them down with a glass of water. He Called Me Brother, Afterwards Cambridge, MA Walking in the middle of the street— The night, clothed in silence. Soon, winds made of human voices Begin to trail me. On the sidewalk of my fear, He stands like an iron gate. In his left hand lays A moon, carved out of stainless steel. In his right, death’s oldest son. You Jamaal, you Jamaal, right? He proclaims. His breath, Already pressing Against mine. I was silent. I mean, what do I know of color Since I’m from a land where even the sun is dark. Answer me now, he barks. I wasn’t, and my school ID is a diligent witness. No need to worry, brother, Jamaal just stole a car, And you look so much like him, he says, Before patting me.

Alan Chazaro My Mexican Abuela Taught Me How to Land on the Moon I’m not sure if there’s ever a perfect. If this light/dark cycle will ever reset. If there was an artificial moon, I’d want to drink its vibrancy in the same way we drink our final moments before they’re gone. These days my circadian rhythm has been rotating against me. Don’t take this negatively; negatives are needed for exposures. I’ve been reading about aliens a lot, how their languages are purely hypo- thetical since none have ever been encountered. When I first kissed my abuela’s language, I felt like I was floating on a third moon. Some people believe we’ve never even landed on the first moon. Some people think the world isn’t really globed. I don’t believe in flatness and I rarely consider gravity unless I’m falling. I don’t believe in certain languages, certain oppressors. Have you ever been so bored with your reality that you created a future that didn’t make sense? Recently, a city in China proposed to build a replica of the moon and hang it like a photograph framed in the night sky. They said it would hold the city’s light in times of darkness to conserve energy. What if conserving energy was actually a bad thing? What if we never learned to cleanse our mouths of whatever needed saying? What if we always hid from our darkest hours? I guess I’m not sure if there’s ever a perfect moment. If aliens can actually form sentences from nothing, or if we simply imagine what we want—impossible forms of comfort. When my abuelita passed, I didn’t cry. She gave me an impossible comfort from two feet away. She gave me many moons in my palms. When I need her, I return to their many surfaces. They keep me grounded with impossibilities. In 2020, the 45th President of the United States Declares, When the looting starts, the shooting starts, Meaning: We Can No Longer Breathe In America Meaning: we are not the same. Meaning: the lights have literally been turned off in the White House. Meaning: there is no room for figurative interpretation. Meaning: where is our leadership? Meaning: why do we keep burying our own bodies in our own dirt? Meaning: there is not enough space for more of this. Meaning: yesterday I was marching with families and children and teachers and teenagers and wives and husbands and my grandmother-in-law from New Mexico said, This country is just lost in a big chaos. Meaning: we are not well, we are not okay. Meaning: a neck bone can collapse from a forcefully applied knee. Meaning: some things can never be replaced. Meaning: there is division, and there is negligence; where are you? Meaning: we’re talking about a man who was murdered on video. A man who was murdered on video. A man who was murdered on video. A man who was fucking murdered on video. Meaning: some Americans don’t care until their windows are broken, then they are bothered. Meaning: our future cannot look like this. Meaning: I refuse. Meaning: we will all be saved or we will all burn together. Meaning: I swear to every god I will work for a different world, because Pocho boys can build spaceships, too. Meaning: we can no longer breathe in America. Alternate Universe Ending #2 In this version I am riding an all-black single-gear bike along Lakeshore Ave near my apartment, and a cadenza of dusk is singing a nearby family of trees into a deep chorus of green that can only be described as baptismal, as if our bodies might be simply and impossibly loosened into a wild dance of light- shadows, and in this moment I am taken by a bloom of faces around me, and I cannot tell if I am pedaling forward or being pulled on a string, and if there is a string how it must stretch from far beyond wherever this sidewalk ends, towards some parallel galaxy I have no business entering because I am no cosmonaut, and I am unsuited for this, and I am just a boy who watched too much Star Wars growing up and how, if I go too far past what I know, it might unravel me.

Jee Leong Koh The Father for W. (Chengdu House, Chelsea, New York, March 6, 2019) What was compassion he learned when he helped his older son fill up his college forms. He wasn’t so neglected his abuela had to report to Children’s Services. He didn’t grow up in a foster home. He hadn’t, every season, to meet strangers, before he graduated out the system, to play basketball, to make them like him, afraid the whole time they would make him choose between a real home and his younger brother, or su hermano would choose home over him. What would Admissions think of his expulsion from school for selling his classmates his meds? What of the second time he had to leave, this time from boarding school, in the same year as Trump’s election? Rapists, criminals, the President labeled all immigrants. Not long ago the same slander applied to men who lived with men and wanted sons. In Singapore, the technocrat’s wet dream, he chose and was, it seemed, chosen, by merit. Coming from no-name school to RJC, he thought the students smug. Instead of joining Humanities, he chose Arts stream to root for local faculty. Instead of the Ivies, he studied fashion at Parsons. Instead of the Chelsea boy, he dated older men, much older men, with stories of surviving conversion therapy, gay bashing, AIDS, heroic stories of protest and care. He met his husband on Craigslist. He googled the value of his home to judge it safe, as he had always done. He didn’t know about the shootings in the neighborhood. So much for Singapore-style planning! How could he imagine in one year he would marry in February, graduate in May, and in June have the boys move in with them? He had always been good at being trained and the adoption training was not hard, good at filling up forms, following rules, at cost-and-benefit analysis, but he had to be taught again and again, by Christmas cacti as well as the boys, their shooting, flourishing, yet homely needs informing his attention, the feeling of fear inalienable from fatherhood. On Graduating from Your Play-writing Program for Zizi Azah The times, they are against you, the Times too, the chummy virus has closed down the lights, for how long not one prophet can be sure, and afterwards, if afterwards has rights, the patient is unhooked from machine lungs, totters, collapses here and there, eyes whites, a modern Zinira whose mother tongues holler unheard. Distant are the satellites. Writing for TV is an option close to blasphemy, betrayal, or bad works, much as one loves the silver cellulose, much as one envies its heroes and its jerks, for live theater is bang on the nose, not the image of faith but faith itself, precise and literal and malodorous, transforming us into a commonwealth. We need plays! We need playwrights! The old term recalling still of mills, wheels, ships, and carts. Although the wilderness glares and grunts, be firm! Glare back until the One who sees our hearts brings to your side the tiger and the tick, turning all counters into counterparts. Grunt if you must, because the work is sick, but Prophet you’re, and Mistress of the Arts. The Conductor for Phillip Cheah, born in Louisiana, 1978. He never saw her without make-up on his pretty mom who had a different hairdo in every photograph she left behind. Stylish as she was, he never left home without his Brylcreem helmet and his suit, well favored by the flower of a tie, Anita Mui from her radio in his ears. A misfit with his peers, he gravitated to teachers, who in every year made him a monitor in Rosyth and RI. The love of music begun at puberty, after some years of banging ivories, when he was taught composers and their times and music gathered faces and debates, closeted Phillip further—Tchaikovsky!— in Yamaha’s CD library near Balestier. The blissful hours lost in listening, listening, listening, and listening. His father, the geophysics engineer, wanted to give his draftee son a choice: go Singaporean/stay American. Music, like his mom, did not give him one. No conducting school to go to here, everyone played the piano or violin, and to conduct was what he was to do. At nineteen, the boy flew to Bloomington, Indiana, to take up his birthright, failure propelling him with fearful fumes, first in the country of Bernstein, and then his city, charging hard from gig to gig, rising to direct the Central City Chorus while he accompanied New York’s elite in tuning up their vocals for the world, where we met, when somebody (was it Karyn?) told him, funny coincidence, there was another Singaporean in the school. As the intent for tempo clarified from Beethoven onwards, the instrument changing from heartbeat to the metronome, so we discovered the disparate ways by which we know the same Alvin Tan, teacher to you and paragon to me. What we talk about when we talk about mothers is meter, the stress on the beat, the knuckles, violent roses, that you raise in concert with your slim baton, and that she caned to make you learn to tell the time.

Issue 1 – Detroit

Peter Markus Too Many Days, or Where the River Turns to Lake It has been three days since he's seen the river. Three too many days if you ask him. To be inland means in from the river. There is a river running inside of him. For the past few years he had his father to go see before walking down to the river. Now he has his mother he goes to see in her grief. Let's go down to the river is what he tells her, and he takes her by the arm to safely walk her down. She watches him fish. She is momentarily happy, it seems, when he catches something. It's not what he's fishing for but it's a fish regardless. He throws what he isn't after back. His mother asks about the hook. Doesn't it hurt. He makes up what he thinks is possibly true. That the fish do not feel pain. That they don't have nerves in their lips which is where the barbed hook takes hold. He doesn't know for sure if this is true. He knows that if a lie is repeated often enough it begins to carry its own truth. Today the geese are grouping up on the river, preparing for some migratory trip. They make their loud honking sounds though his mother does not turn her head to hear them. She is elsewhere inside her own thoughts, he knows. She is somewhere, he hopes, with his father, on a boat, perhaps, like when they were both still young, without kids, with the wind filling their sails, pushing them out of the river, into the bigger lake.

Nancy Owen Nelson

“Say Hey, Willy!” Says Spencer Turnbull,

Opening Day, Detroit, Michigan,

April 4, 2019

Willy, I heard you came from Alabama too, like me.

I was not actually born there. Born in Mississippi,

but Alabama’s my home, since I played the ‘Bama team.

Like me, you made it big out of a little place,

scored 7-0 against the Houston Colts one summer

evening, 1963. You were before my time but

I saw you in a dream last night, sitting silent on the bench,

chewing gum, or was it tobacco? Waitin’ for your turn

at the bat. Heard an old man in the stands shout “Say Hey

Willy!” and climb slowly down the bleachers to get

your John Hancock on a game program. That old man

walked slowly, I said, careful that he might not fall.

Willy, you were important to him, the old man

in a fedora, grey with the bill turned up. His face

earnest, he grinned as he yelled “Say Hey, Willy”

yet again, makin’ sure he got your attention.

Makin’ sure he got your signature on the program.

Makin’ sure his 16-year-old daughter would not

be disappointed. That old man was from Alabama

too, like you and me. Had been through wars,

seen too much. Worried about his daughter, who

held her silence close to her, like hugging a secret

to her chest instead of calling out your name for an autograph.

Too bad, he thought, that she’s too scared to seize

the moment. To find her hero. The old man had

seen too much, Willy, about what they did

in Alabama to folks like you because of your color.

He yelled “Say Hey, Willy!” to let you know that,

though his skin was white, he’d seen some awful stuff.

And he was on your side.

So here I am, Willy, in Detroit on this big day,

pitching balls. Had ten strikeouts, ten Royals

walked away from plate, dejected. No one said

“Say Hey” to any of us, but inside, I knew you

would be proud for me, proud I came from

Alabama, proud I love God and good works,

proud I want to go to Uganda with Tigers pitcher

Matthew Boyd, help those kids caught in the slave

trade. I think the old man in the bleachers would be

proud of both of us, the Alabama boys who left

home and made good in the world. Did good for folks

like kids in your “Say Hey Foundation,” kids in Uganda.

I think the old man would grin his sideways

grin, hope his daughter would understand

we’re on the same side.

Cal Freeman A Liquidation of the Portraits of the Saints for Larry Larson Your eyes were the glass of another city’s buildings the last day I saw you. You’d become a drug addict, you said, a realization that came while taking an extra pill that afternoon and watching the flurries drift down the street like avid businessmen. The tremor in your hand quieting with the first payload, you were a gaunt face in a cold pool of coffee. They’d carved out half your left lung to get the cancer and prescribed Oxycontin while radiating your lungs and vocal cords, but it had been months since you needed pills for pain. This was to be kept strictly between you and me, but it’s true, and impossible, anyway, to libel even the newly-dead. I picked up your Gibson J-45 and strummed the chords to a new song. Fret three was a cicatrix of grime where your middle finger pressed to make a G, 30 years of that in smoky stage lights. You kept a Gatorade bottle full of vodka next to your volume pedal, nobody wise that it wasn’t water. That guitar thirsted in arid Michigan’s late-winter (the furnace coughing on at intervals), its finish spidered like a mess of varices. The health of things no more than the hum of mahogany and spruce, lungs, gallbladder, bone bridge, brain, heart, and spleen (a splenetic cadence to your voice) despite what we believe. The hook was, “Just another disappearing thing,” erstwhile Detroit, bars with silt-smeared windows where you cut your teeth picking sad songs on a Guild 12-string while your friend Eddie McGlinchey sang ballads about those Irish heroes of ‘16 whose portraits you’d later paint. That last gig we played together in January you sang better with half a lung than I ever will. You said you were proud of me and asked if you could pat me on the chin, that Bob Gibson had patted you on the chin at the Raven Club in 1963 after realizing you’d mastered his finger-picking technique (pinch, thumb, pointer, thumb, middle, thumb, that measured thump on alternating bass strings). Bob Gibson who’d destroyed his talent with heroin and amphetamines, who even after kicking never got right again. They say the frontal lobe irredeemably changes. Too much is irredeemable. Can I pat you on the chin? You who knew everything about the faces of flawed saints and bitter heroes. You’d just painted Father Solanus Casey for perhaps the seventh time. You said his expression carried knowledge from another place. This version featured a halated Blessed Mother in the foreground with a backlit Calvary nearly vanishing the way a phosphene behind a closed eyelid can turn consciousness sacramental. It didn’t matter to you that it was good. Nothing mattered much those final weeks. They auctioned off your instruments and artwork at the wake. The afternoon light bleared through the open door bald as a single-payload pill each time a mourner came to buy a piece.